By Ben Crosbie

With the Panasonic AF100 having just been released, and Sony having announced two new S35 video cameras, how does an indie film-maker decide on what camera to use for their next project? DSLR, AF100, NXCAM, F3 (if you can afford it) – such a wide array of choices that many of us would have never imagined could exist 5 years ago. Now instead of struggling with clunky 35mm adapters for your 1/3″ camcorder, you can simply pick up a DSLR or the forth coming Panasonic/Sony camera, attach a SLR lens and hit record. You’ll be rewarded with a filmic depth of field, expanded dynamic range, and incredible low light capabilities (previously you only gained 35mm DOF with the adapters.) So which camera do you choose?

Our Choice

We just got the new Panasonic AF100, and had picked up a Panasonic GH1 a month ago as a B-camera and to use in the gap prior to the AF100’s release. In a previous blog I had said that we were not going to use a DSLR for film-making, but obviously we have reneged on that decision. We were all set to shoot our new projects on the AF100, but a few had to begin a couple months prior to its release. As a result, we decided we would try out the GH1.

While the Canon 5D MkII was one of the first DSLRs used to shoot video, and remains king of hyper shallow DOF (thanks to its massive full frame sensor), we decided against using it for a few reasons. We opted for the GH1 because it’s cheaper ($1000 for body and video optimized lens vs. $2400 for the 5D body alone), and because we would easily be able to share lenses between the GH1 and the AF100, and the two would cut together much more easily. Additionally, older models of the GH1 can be hacked to improve the bit-rate (and perhaps one day the newer models as well), and even without the hack, the GH1 works much better for shooting video. It has no limit on recording times, includes typical video frame-rates and a good articulating LCD screen and high quality view finder that can be used while recording video (unlike the other DSLRs that have mirrors preventing the use of the viewfinder during recording.) The 5D (and 7D, 60D etc.) all offer some advantages over the GH1 for certain users and purposes, but for us, the net advantage went to the GH1.

Shooting with the GH1

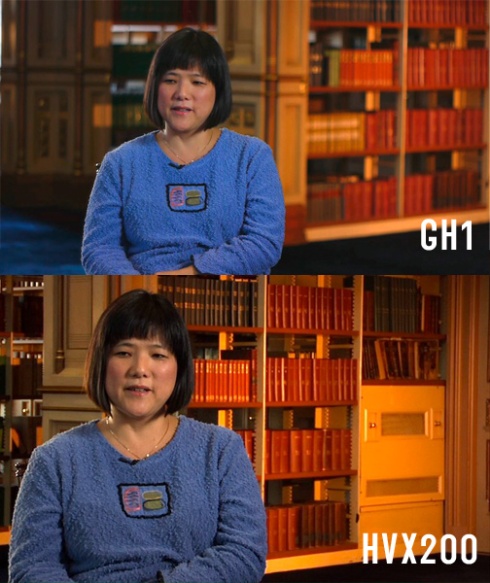

Our GH1 is unhacked due to it’s build date, so we are only seriously considering using it for sit down interviews and staged B-Roll/artistic scenes. I have no real desire or plan to use the GH1 for any run & gun action, fast-moving subjects, wide shots or the like. That is what the AF100 will be for. So how did the GH1 work out on our recent shoot? As a video camera, the GH1 is not perfect. Like any DSLR, it is not meant to shoot video, so it lacks some essential features found on “real” camcorders. Exposure tools like zebras, waveforms, XLR audio, and timecode are all absent from the GH1. It also lacks a video out port that you can connect to a pro monitor. So judging exposure with the GH1 can be scary to say the least. You have to really trust your eyes and have enough experience with it to know what you will end up with. All that said, the images it produces can be spectacular. We shot 12 sit down interviews with the GH1, and all of them looked gorgeous. We were able to get some shots that we were physically incapable of filming just one year ago with an XHA1 in the exact same shooting locations. We shot a 2nd camera with an HVX200, and the side by side difference is actually quite stunning:

The lower quality AVCHD of the GH1 didn’t really present any problems with these types of shots. In underexposed areas there were some artifacts, but the GH1 still outshines the HVX200 in pure aesthetic quality.

The AF100

We pre-ordered the AF100 a couple days after it went on pre-order. “How can you buy a camera sight unseen?” you may ask. Well, the last camera we bought (Canon XH-A1) we purchased without ever having used it, and I would venture to say most people never get to touch, let alone test extensively, any camera they are buying. You have to make the decision based on reviews and specs. The AF100 doesn’t have any reviews really, aside from pre-production model tests which have sent some into a tizzy about highlight clipping, lack of dynamic range and a “video-look.” The footage I’ve seen from the test shots look amazing, and the earlier testers are all in love with the camera, so I stand firm in my decision to pre-order.

The AF100 offers everything the DSLR users have come to love, but leaves behind all of their short comings. I consider this a game changer, but many do not. Many are expecting this camera to deliver some amazing new “never-before-seen” imagery, but that is just unrealistic. I’m not sure what that would even look like. The AF100 will give us the same filmic image we have come to expect from DSLRs, but without moire, aliasing, skew, and with the addition of proper video features such as long recording times, proper audio, proper monitoring, outputs and lots of buttons to control all the functions. This is exactly what we need. We need a camera that works like a real video camera, that can be trusted in a variety of situations, and doesn’t need a multitude of accessories to function properly. The AF100 promises to fit that bill.

First Test Shoot

Today I was able to take out the AF100 for a test shoot. This was my first time using the camera, so I still have many things to learn about it. But my first impressions are very high. The camera is a dream to use. Functionally, it works just as any prosumer camcorder should. It has all the right tools, knobs, and functions for creating good looking video, and allows you to do it easily. That is the key thing I noticed from the test shoot. I never found myself once wishing that I had some extra feature. I had all the tools I needed at my disposal. This is how using a video camera should be. The LCD is quite large and sharp, and I rarely had focusing issues due to the handy focus-in-red feature. The built in waveform also helped enormously in judging tricky exposures.

The footage the AF100 produces is also very, very nice. It resembles the GH1, but has the much better broadcast version of AVCHD. This means it has a higher bitrate and many more compression key frames which allow the codec to withstand more challenging situations in which the GH1’s codec would fall apart. The AF100 also has variable frame rates up to 60fps at full 1080p. This is huge feature for a camera in this price range, and let me tell you, the 60fps stuff looks awesome. I have many more tests and shoots to do with the AF100 before I can really comment on the quality of the footage, but so far I am impressed, and you can judge for yourself:

Filming children can be fun and can result in some heartwarming footage that anyone with an ounce of humanity will find endearing. Filming children can also be a nightmare, that can result in endless lawsuits. Ok, you probably won’t get sued if you film a child, but there are huge legal ramifications when it comes to filming children. While anyone can film a child in public if he so chooses, it’s mainly the public display and/or distribution of such footage that causes the legal problems.

Filming children can be fun and can result in some heartwarming footage that anyone with an ounce of humanity will find endearing. Filming children can also be a nightmare, that can result in endless lawsuits. Ok, you probably won’t get sued if you film a child, but there are huge legal ramifications when it comes to filming children. While anyone can film a child in public if he so chooses, it’s mainly the public display and/or distribution of such footage that causes the legal problems. The boys first made silly faces in front of the camera, or simply stood and smiled. But after a few minutes, they became disinterested with our presence, and continued their play. Ben used his limited Hebrew to ask them open-ended questions about summer camp in the kibbutz, but they gave one word answers. We asked Leah to question the boys using her fluent Hebrew, but their responses were not any more expansive. They are clearly too young to fully reflect on their childhood. But their largely unsupervised, free, creative play spoke volumes of their childhood.

The boys first made silly faces in front of the camera, or simply stood and smiled. But after a few minutes, they became disinterested with our presence, and continued their play. Ben used his limited Hebrew to ask them open-ended questions about summer camp in the kibbutz, but they gave one word answers. We asked Leah to question the boys using her fluent Hebrew, but their responses were not any more expansive. They are clearly too young to fully reflect on their childhood. But their largely unsupervised, free, creative play spoke volumes of their childhood.